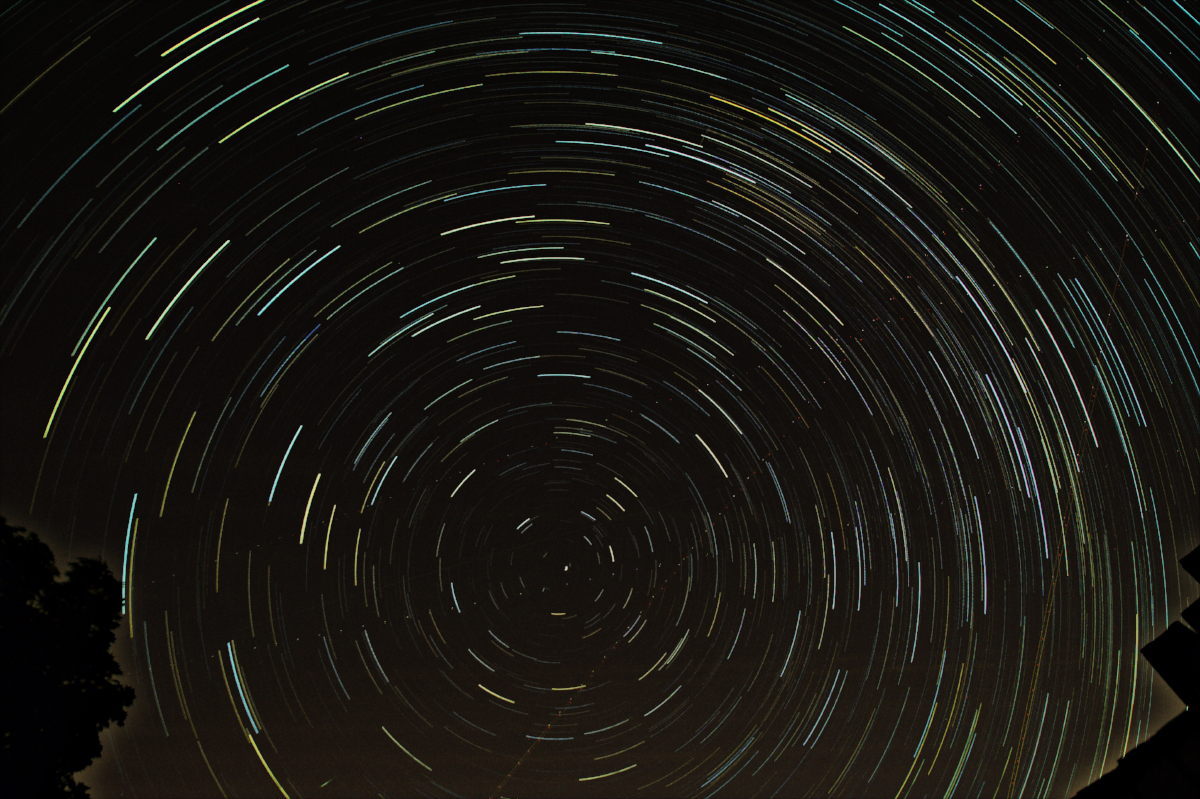

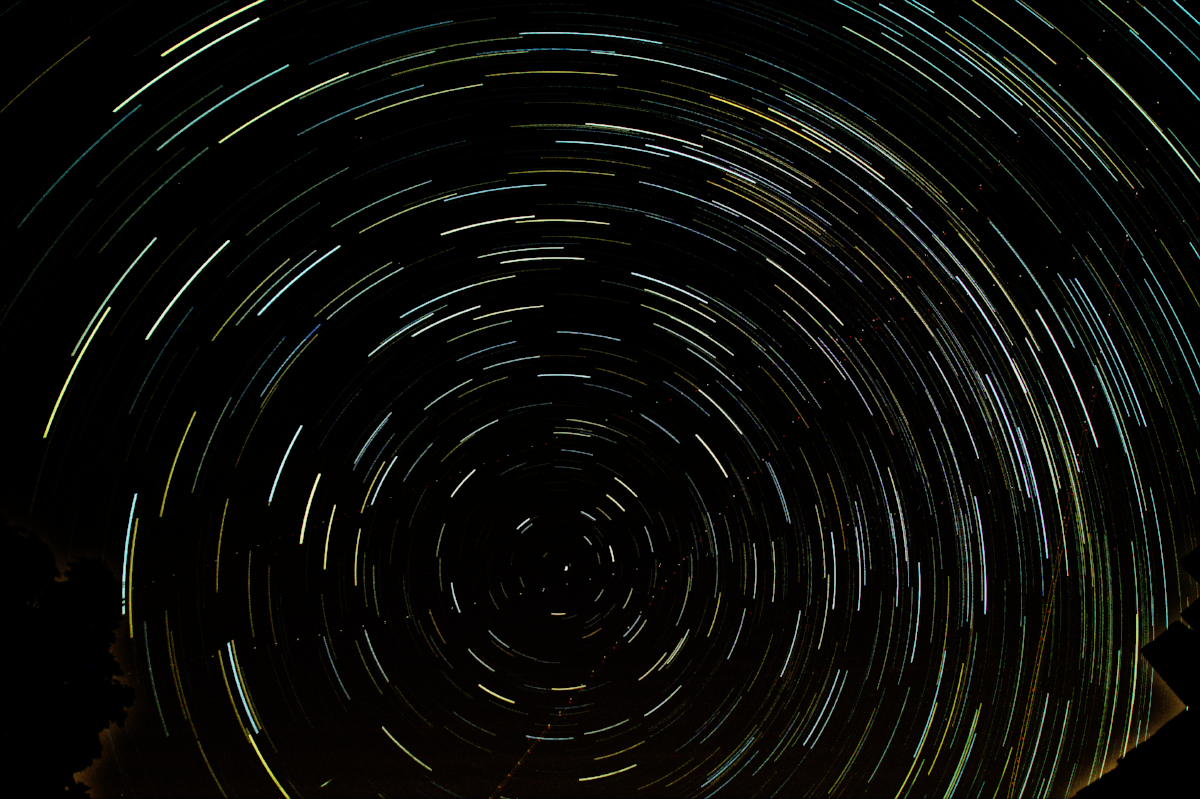

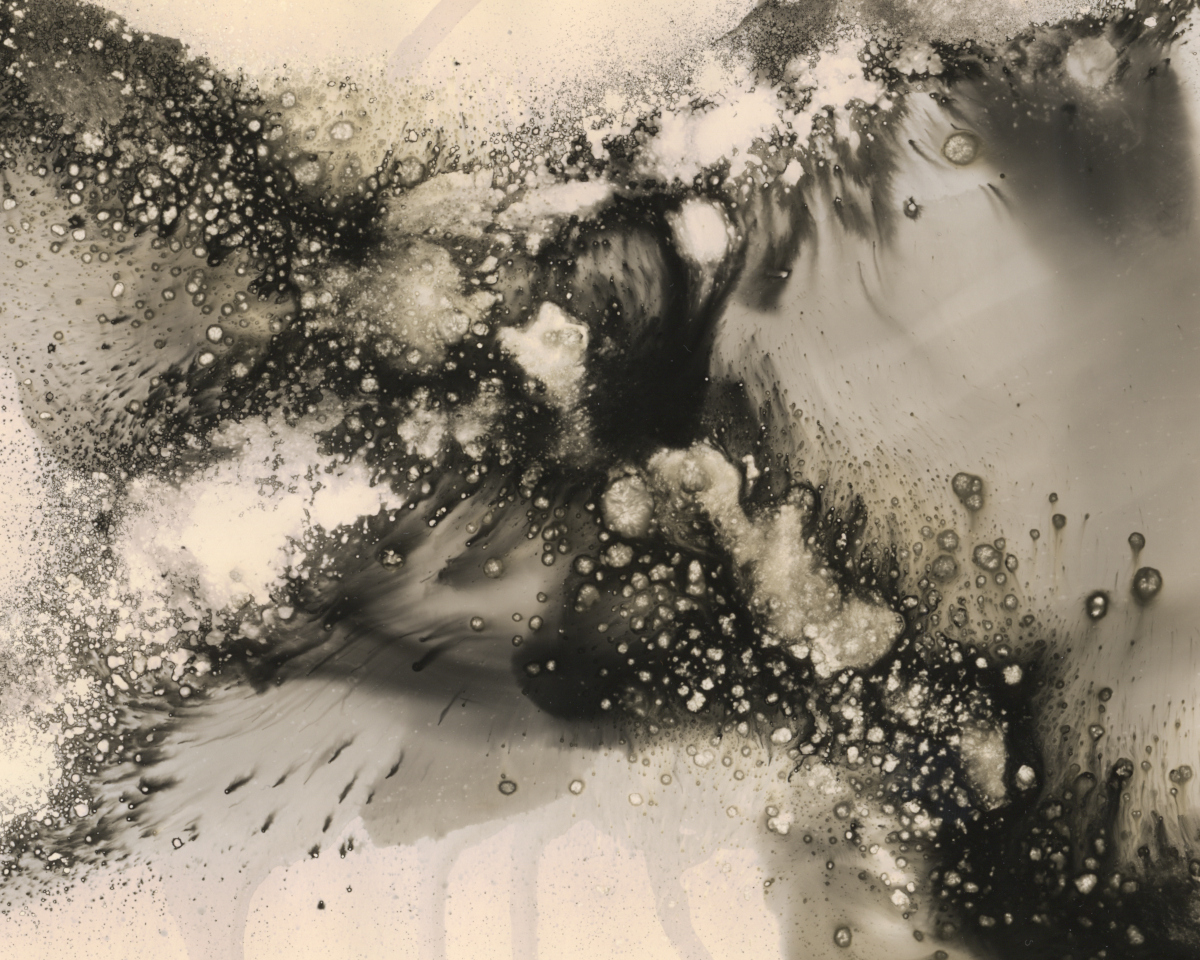

The cyanotype and lumen printing processes are two of the more frequently practised alternative photographic processes, because of their overall simplicity and the fact there is little-to-no need for equipment. Most people will do their exposures outside in the Sun initially, but if you want to work with these processes on a regular basis it can be frustrating to have ideas ready to try, but be delayed by lack of a sunny day. While it is still possible to expose on cloudy days, the length of time required to obtain a suitable image is greatly increased. Working with the sun it is also difficult to figure out predictable exposure times as the intensity varies according to the daily weather, time of day and time of year.

The solution is to switch to an artificial UV light source which can be used any time of day or year, whatever the weather, always giving the same exposure time. Historically though, UV exposure units have been relatively expensive to obtain, £100 or more. The ongoing developments in LED lighting technology though have now opened up new possibilities for constructing a custom UV light source for minimal cost. In particular it is possible to obtain 5m long strips holding 300 UV LEDs from online marketplaces such as eBay, for around £15 / $20 (search eBay for keywords “5M UV 5050 SMD 300LED“).

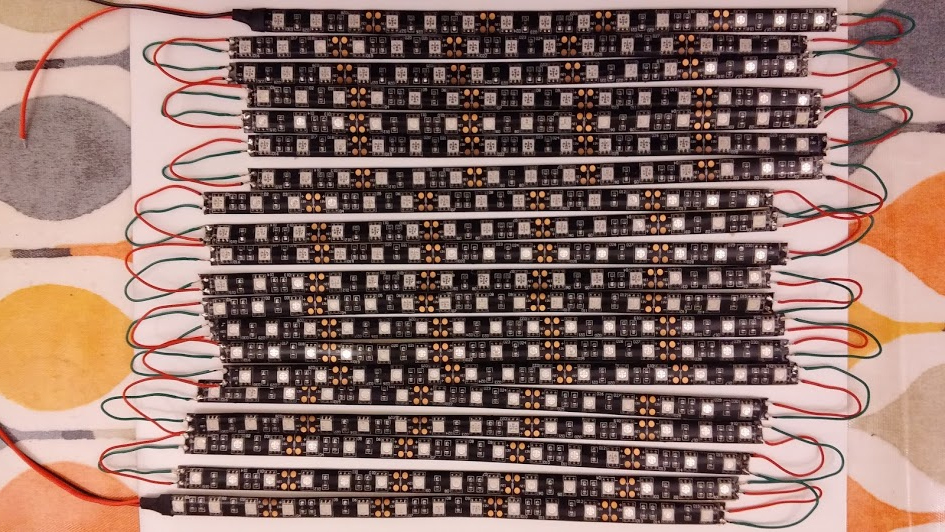

The 5M long 5050 LED strips are 1cm in diameter and can be cut every 3rd LED. If they are cut into groups of 15 LEDs, this will result in 20 LED strips, each 25 cm long. Arranged side by side, this allows for creating a light source that will evenly expose a 20 cm x 25 cm area which is practically perfect for both A4 and 8x10in paper sizes. If one didn’t mind lower intensity it would be possible to left a 1cm gap between strips producing a source suitable for 16x20in / A3 paper, at the cost of longer exposure times.

When cutting the LED strip up, it is important to cut exactly in the middle of the metal contacts between every 3rd LED, as it will shortly be necessary to solder wires onto the metal contacts. If using the waterproof coated LED strip, the rubbery coating will have to be removed from the contact pads after cutting, which is quite tedious and an argument in favour of the non-waterproof variants. With the strip cut into pieces, it is now time to connect them back together by soldering short (5-10 cm length) wires between the metal pads. While it is possible to wire them all together in series to form one long strip, this means the link wires will be carrying the full 5 amp current load and if any link goes bad it risks taking out the entire set of LEDs beyond it. A better bet is to wire them up in parallel, or perhaps grouped in a mesh giving multiple paths for the current, so the link wires only need handle a tiny current and there is redundancy. The important thing when soldering the link wires is to preserve the polarity between strips – ie connect positive to positive, and ground to ground.

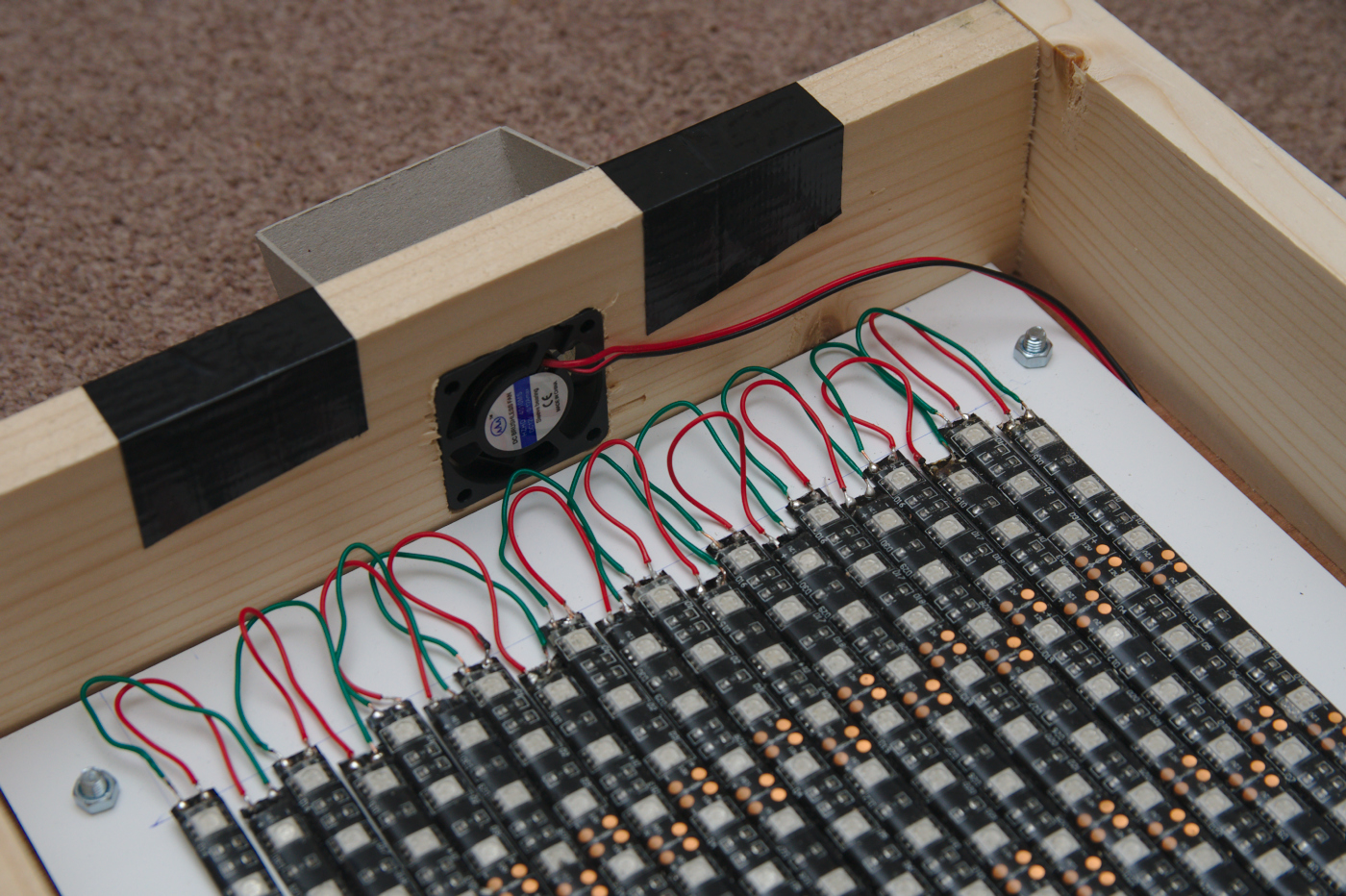

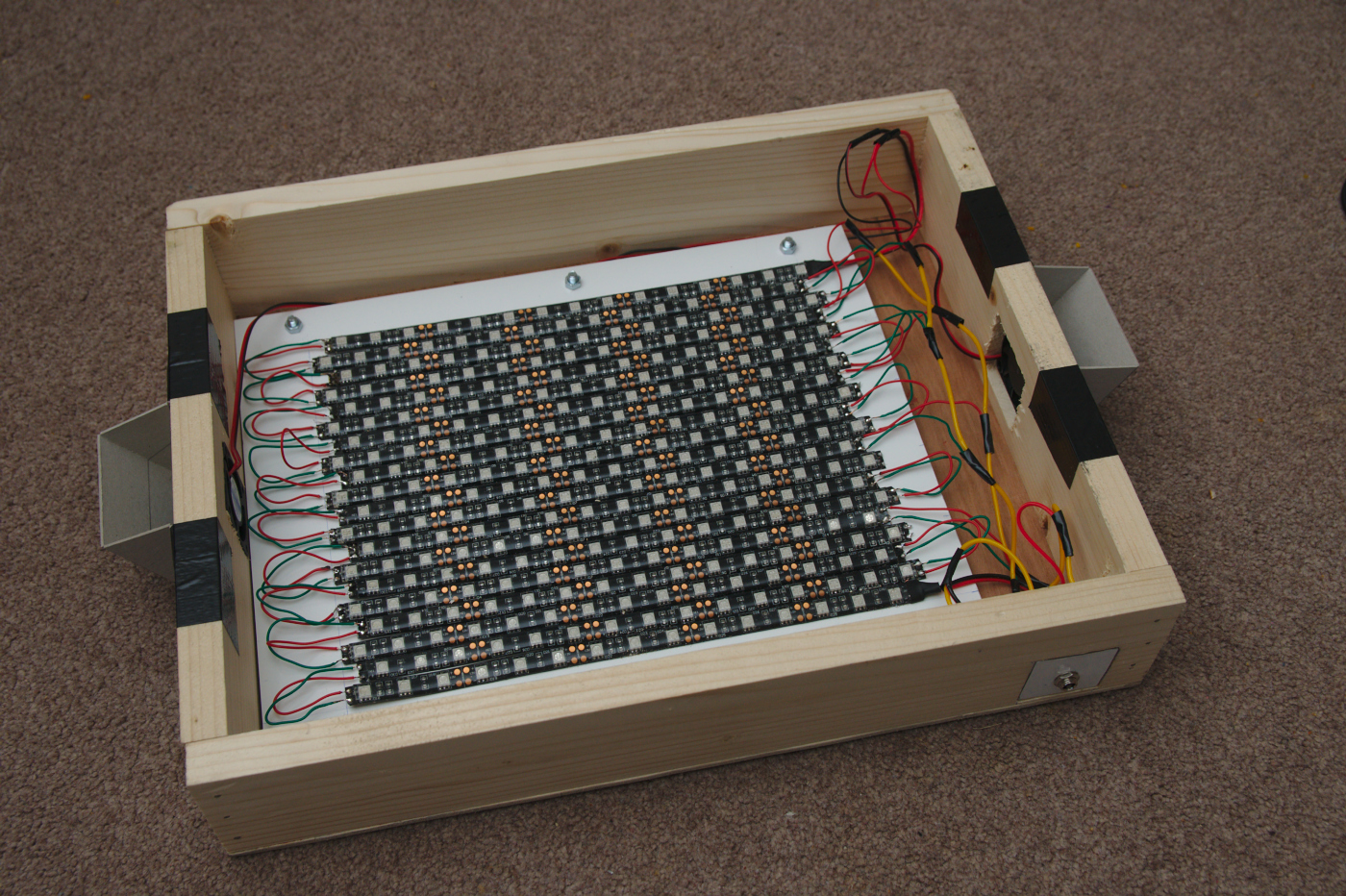

All 20 strips with connecting wires soldered on. Mistakenly all 20 strips are in series. This was later resoldered to split them in 5 groups of 4 strips, each group in parallel, reducing current in the link wires to 1amp.

The vendors of the LED strips will typically also sell suitable power supplies. These mains powered units need to output 12 volts and be capable of supplying 5 amps to enable the LEDs to run at full brightness. Lower amperage PSUs will work, but the reduced LED intensity will obviously increase exposure times, so it is best to simply get the right specification of PSU from the start.

The power supply will likely have either a 2.5mm or 2.1mm plug, so a correspond matching socket needs to be purchased. While it is possible to just turn the device on/off at the wall, or by pulling the plug out, a better bet is to put a rocker switch inline with the positive power line between the plug socket and the LED strip. Again make sure the rocker switch is rated to carry 5 amps.

Power output is given by multiplying voltage by current, so 12 volt at 5 amps will produce 60 watts of power output. This is going to generate a reasonably large amount of heat and if something is not done about this, it will gradually degrade the LEDs shortening their lifetime. The obvious answer to this is to obtain a couple of 12 volt computer fans to fit in the case of the final light box. A fan that is approximately 4cm x 4cm in diameter will be ideal. They’re quite cheap so you might even consider using a pair of fans. The wires from the fan can be connected in parallel with the LED strips, since they’re conveniently driven from the same voltage. Do NOT connect them in series with the LEDs, as the 5 amp current draw of the LED circuit will kill the fans. Also be careful to get the positive/ground polarity right when connecting the fan, as reversing polarity will NOT make the fan run in reverse and likely kill the fan too.

The case for the light box will be made out of wood and comprise two pieces, a base which will hold the paper to be exposed and a slightly larger lid which will hold the LED panel. Both will have sides and be sized so that the base nests snugly inside the lid (or vica-verca). The top and bottom panels can both be cut from a sheet of 3mm plywood, the lid panel being 39×30.5cm and the base panel 36.5×25.5cm. These sizes are fairly arbitrary – the smaller simply needs to be about 2 inches larger than the size of paper to be exposed on each side. So for 8×10 paper, the smaller would want to be about 12×14 inches. For the larger lid, sides were cut from a length of 70x18mm timber, and nailed to the plywood panel. For the smaller base, sides were cut from a length of 36x10mm timber. In the timber sides of the lid, two 4x4cm holes were cut to hold the fans. Two holes were also drilled in the lid, one for the power supply plug socket and the other for the on/off rocker switch. When inserting the fans in the case, one should be oriented so that it sucks air into the case while the other should blow air out of the case, creating good airflow across the LED panel.

Light box lid showing the on/off rocker switch through the panel and power supply socket in the side

Close up of the lid, showing the computer fan inserted in the side to pull air across the LEDs for cooling.

The LED strip usually comes with a self-adhesive backing tape which is supposed to be able to stick the LEDs to most surfaces. This proved insufficiently sticky for me, so I applied super-glue instead. While the LED strips could be attached directly to the lid of the light box, it was thought preferable to attach them to a sheet of perspex or aluminium to allow the LED sheet to be separated from the case if needed. If using metal just be careful to avoid any short circuits with the link wires of the LED. Once the LEDs are attached, the sheet can be fixed to the inside of the lid with a couple of screws.

The larger lid, showing the metal plate with LED strips attached. At either end are cardboard shields to block UV light leakage through the fans.

The smaller lightbox base, sized to be able to hold an 8×10 inch picture frame from a pound shop. Note a couple of screws sticking out of each side of the base, to prevent it sliding completely inside the lid when nested

When first turning it on, there was some UV light leakage through the cooling fans. Thus a couple of shields were cut from heavy duty cardboard and duct taped over the fan openings. With this in place there is no significant UV leakage from the light box, due to the closely nested lid and base. The UV LEDs are emitting at the end of the UVA spectrum, quite close to the start of the visible light spectrum, so the light is not a serious danger like UVB light would be, but it is none the less worth taking care to avoid accidental exposure.

In use the light box has proved to be intense enough to expose acceptable cyanotype images in as little as 5 minutes, and lumen images in anywhere from 10 minutes upwards depending on the visible effect desired. This is considerably faster than many commercially obtainable UV light sources that photographers have used in the past, which could take 15 to 30 minutes or even more. All together the cost of the complete box was probably around £45 – if you already have some parts in the shed such as plywood / timber pieces and a suitable power supply, then the price could be around £20-25. Either way, it will easily beat the cost of commercially produced light boxes and likely perform better too. The hardest part in construction is probably the soldering of the 50+ link wires between the LED strips. The case needs only minimal wood working skills – use of a saw and hammer. In summary creation of the light box is a very worthwhile use of time and money and will proof useful for years after.