One of the critical problems when producing astronomical images is to minimize the amount of noise in an image, while still being able to capture the very faint detail which is barely distinguishable from noise. The post processing technique used to address this problem is to merge together multiple images of the same subject. The constant signal in the images gets emphasized while the random noise gets smoothed / cancelled out. There is specialized software to perform stacking of astronomical images to deal with alignment between subsequent frames, as the earth’s rotation can cause drift over time if the camera mount isn’t compensating. The image stacking technique is not merely something for astrophotographers to use though, it is generally applicable to any use of photography.

Image stacking in a non-astrophotography scenarios is in fact simpler than one might imagine. The only physical requirement is that the camera is fixed relative to the scene being photographed, which is trivially achieved with a tripod of other similar fixed mounting facility. In terms of camera settings, it is necessary to have consistency across all the shots, so manual focus, fixed aperture, fixed shutter speed, fixed ISO and fixed white balance are all important. With the camera configured and the subject framed, all that remains is to take a sequence of shots. How many shots to take will depend on the quality of each individual image vs the desired end result. The more noisy the initial image, the larger the number of shots that will be required. As a starting point, 10 shots may be sufficient, but as many as 100 is not unreasonable for highly noisy images.

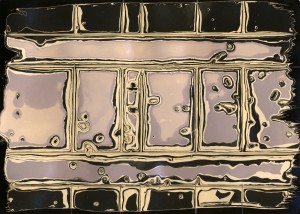

To illustrate the versatility of the image stacking technique, rather than use images from my DSLR, I’ll use a series captured from the night vision webcam of the Wurzburg radio telescope. A single captured frame of the webcam exhibits large amounts of random noise (click image to view fullsize):

Over the course of a few minutes, 200 still frames were captured from the webcam. The task is now to combine all 200 images into one single higher quality image. Processing 200 images in a graphical user interface is going to be painfully time consuming, so some kind of automation is desirable. The ImageMagick program is the perfect tool for the job. It has a option “-evaluate-sequence” which can be used to perform a mathematical calculation for each pixel, across a sequence of images. The idea for minimizing noise is to take the median pixel value across the set of images. Stacking the images is thus as simple as running

# convert webcam/*.jpeg -evaluate-sequence median webcam-stack.jpeg

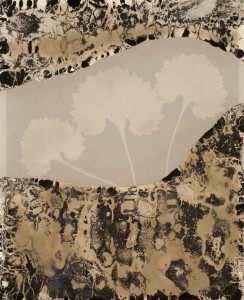

This is pretty CPU intensive process, taking a couple of minutes to run on my 8 CPU laptop. At the end of it though, there will be a pretty impressive resulting image:

The observant will have noticed the timestamp in the top left corner of the image gets mangled. This is an inevitable result of stacking process when there is part of the image which is moving/changing in every single frame. In this case it is no big deal since the timestamp can either be cropped out, cloned out, or replaced with the timestamp from one single frame. In other scenarios this behaviour might actually work to your advantage. For example, consider taking a picture of a building and a person walks through the scene. If they are only present in a relatively small subset of the total captured images (say 5 out of 100), the median calculation will “magically” remove them from the resulting image, since the pixel values the moving person contributes lie far away from the median pixel values.

The observant will have noticed the timestamp in the top left corner of the image gets mangled. This is an inevitable result of stacking process when there is part of the image which is moving/changing in every single frame. In this case it is no big deal since the timestamp can either be cropped out, cloned out, or replaced with the timestamp from one single frame. In other scenarios this behaviour might actually work to your advantage. For example, consider taking a picture of a building and a person walks through the scene. If they are only present in a relatively small subset of the total captured images (say 5 out of 100), the median calculation will “magically” remove them from the resulting image, since the pixel values the moving person contributes lie far away from the median pixel values.

Going back to our example image, the massive reduction in noise can be clearly seen if viewing at 1:1 pixel size with the two images adjacent to each other

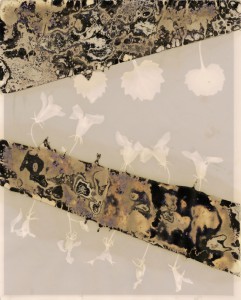

With the reduction in noise it is now possible to apply other post-processing techniques to the image to pull out detail that would otherwise have been lost. For example, by using curves to lighten the above image it is possible to expose detail of the structure holding up the telescope dish:

So next time you are in a situation where your camera’s high ISO noise performance is not adequate, consider whether you can make use of image stacking to solve the problem in post processing.

So next time you are in a situation where your camera’s high ISO noise performance is not adequate, consider whether you can make use of image stacking to solve the problem in post processing.